|

for RIA Novosti Moscow, Russia (RIA Novosti) Aug 20, 2010 Fifty years ago, Russia made a huge stride in its quest to send a man into orbit. On August 20, 1960, reporters crowded around two small but sprightly dogs, trying to get a good picture of the triumphant space travelers. Belka and Strelka, the first creatures to return safely to Earth after 24 hours in orbit, live on in the memories of former Soviets, unlike many of their predecessors, whose difficult and thankless work paved the way for the first human in space. At one of the many events he attended upon his return to Earth, Yury Gagarin, the first man in space, joked, "I'm not sure if I was the first man in space or the last dog." Although he certainly was the first man in space, his Vostok spacecraft was not entirely fit for human use when he blasted off on April 12, 1961. The reliability of its systems left much to be desired. The Soviet space program, which began gaining momentum in the early post-war years, was desperately in need of experimental data. Everything scientists and engineers were doing was unprecedented. No one knew what might happen to a living body in the airless, zero-gravity environment of space, or the effects of space radiation outside the atmosphere. In 1951, Sergei Korolyov, the leading engineer in the Soviet space effort, ordered a lab established at the Military Medicine Institute to select and train test animals for suborbital and space launches. Dogs were ultimately chosen as the most suitable test subject. The size of the capsule dictated the choice: no heavier than seven kilos and no taller than 35 cm. Different breeds of dog were considered, but scientists eventually opted for stray mutts. Physicians explained that these dogs' tough life, surviving on the streets on their own from an early age, made them stronger and more "psychologically stable." The first canine launch took place in 1951. The spacecraft structure was simple then - the capsule separated from the booster rocket after gaining the target altitude and descended with a parachute. Of course, it would be impossible to return from the outer space with a parachute. The first dog in space, the two-year-old Laika, blasted off on November 3, 1957. Her spacecraft, Sputnik-2, was to make a long, seven-day orbital flight and was not expected to return. Landing never became an issue, because the ship's temperature control system malfunctioned, and Laika died from high temperatures on her fourth orbital circuit. Characteristically, the Soviet leadership continued to tell the world for a week that the dog was "feeling well," feeding the illusion that they intended to bring Laika home. After a week, Moscow had no choice but to report that Laika was "put to sleep." Laika's spaceship burned up in the atmosphere in April 1958, but the details of the story did not become widely known until 2002. Two years ago, a monument to Laika was erected at the Military Medicine Institute, and a memorial plaque on the building honors Laika as "the first living being in space." Although the regime's clumsy handling of the PR side of the mission harmed the Soviet Union's image abroad, the experiment was a success. Laika's flight proved that a living being can be safely launched into orbit and endure zero gravity. There was no other way to obtain reliable data on this at that time, and there was no shortage of wild theories, with some scientists predicting a collapse of higher nervous functions in a living body in zero gravity. Environmentalists picketed Russian embassies around the world, accusing Moscow of the cruel treatment of animals. Meanwhile, American space researchers were hard at work on their own experiments with monkeys. On May 28, 1959, a space capsule with two female monkeys, Able and Baker, landed safely after a suborbital flight, which the U.S. media incorrectly termed a "spaceflight," implying that it was the equivalent of an orbital flight. In the late 1940s, several monkey "crews" died in a series of suborbital flight experiments. On July 28, 1960, the Soviet Union launched a recoverable capsule carrying two dogs, Chaika and Lisichka. However, their ship's first stage vehicle broke apart 29 seconds after launch. Belka and Strelka were next in line. On August 19, the two dogs successfully orbited the Earth for 25 hours in the company of 40 mice, 28 of which did not survive. The flight went according to plan, and the dogs fared relatively well, although Belka was extremely nervous. The feeding system designed for a zero-gravity environment was also a success. The dogs were fed on a high-calorie jelly, which provided both food and water. The reentry was smooth, and the spacecraft stuck to the planned route, landing between Orsk and Kustanai, just 10 kilometers wide of the mark. The dogs became world-famous as soon as they landed. The Western world was both fascinated and frightened by the Soviet space program: those Russians were doing things no one had done before - intercontinental missiles, then satellites, now returning dogs safely from space. What would they do next? What if they send a man? After the flight, Strelka had six healthy pups. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave one to the Kennedy family, a slight jab at the less successful U.S. space program. Meanwhile, more dogs were launched into orbit under the Vostok space program. Another failed mission claimed the lives of Pchyolka and Mushka on December 1, 1960. Later that month, something truly bizarre occurred. One of the engines failed while launching the next pair, Shutka and Kometa, making it impossible to blast the capsule into orbit. The test capsules usually had a self-liquidation system, which was essentially a bomb, but for some reason, the explosives failed to detonate. The capsule landed deep in the snowy taiga near the remote Nizhnaya Tunguska River. A rescue party had to be sent on an arduous mission to recover the dogs. The rats and insects that accompanied the four-legged astronauts froze to death, but the two mutts came through the four days of severe cold essentially unscathed. The story was later used as the basis for a movie starring the famous actor Oleg Tabakov as a spaceship designer. The only part of the story not shown in the film was the frantic search for experts who could defuse the self-liquidation system. The spring of 1961 was looming on the horizon, as were the words of Sergei Korolyov: "Two successful test launches in a row, then a man!" On March 9, the next dog, Chernushka, survived its flight, followed by Zvezdochka on March 25. The time had come. Boris Chertok, one of the fathers of the Soviet space program, said later: "If we looked at Gagarin's Vostok today, no chief designer would give the go-ahead for the launch. We didn't understand then how big the risk was." So Gagarin was entitled to indulge in some black humor after he landed. He was the eighth to fly under the Vostok program, and only four of the previous seven launches had been successful. Not all the four-legged astronauts gained the same fame as Belka and Strelka. Indeed, some were not even lucky enough to return home. The opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

Related Links - Space Tourism, Space Transport and Space Exploration News

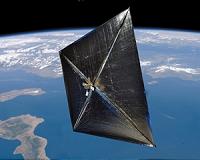

Sailing Among The Stars

Sailing Among The StarsHuntsville AL (SPX) Aug 20, 2010 This fall, NASA researchers will move one step closer to sailing among the stars. Astrophysicists and engineers at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., and the Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., have designed and built NanoSail-D, a "solar sail" that will test NASA's ability to deploy a massive but fragile spacecraft from an extremely compact structure. Much li ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |